We who work in innovation, transformation, change, and all the capital letter functions trying to make the world a better place for you and for me,

It has been a weird journey to understand the cultures around the greater market of ‘I’nnovation. Capital ‘I’ Fancy stuff, that is. Whole world is full of us, it is. You’re probably familiar with how innovation works in your own world already, you are. Likely this post will bore you, it will.

Anyways here goes my attempt at sense making based on all the social media conversations, articles, and interactions I have been able to participate in in my short time in innovation spaces:

Who isn’t innovating these days?

Who isn’t venturing or starting up?

Who isn’t trying to sprint, lean, agile, iterate, synergise, partner and ally?

Who isn’t platformifying?

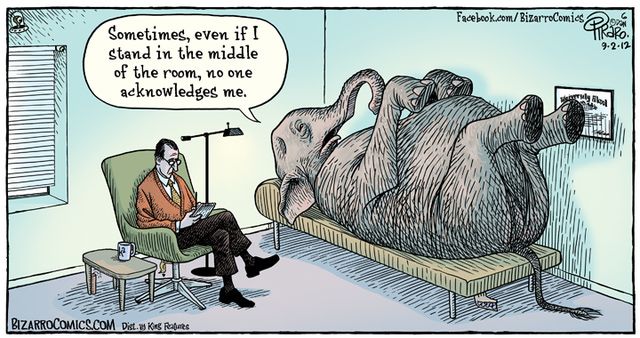

We’re inundated with these words that we’re using so much they are quickly going to be meaningless for us all. (If they aren’t already in our ‘cliche’ box).

The question for all of us is: Who is experimenting?

It is from experimentation that the seeds of innovation grow. It is the brave and lucky who we hold up as innovation heroes. Those who were courageous enough to increase their risk radar to experiment and then kept at it long enough and got lucky to produce value. Those folks are our innovation heroes. There is your Tesla, your Musk, your Edison. They had a process and for some of them it was called the scientific method, a rigorous framework for experimentation.

How can we innovate without experimentation? Can we call it an innovation if someone happens upon a perfectly tailored and commercialisable solution by coincidence the first time? First of all it is doubtful that will happen. Research and development departments, university research labs, most of science, and some of design have all put forward their own specific ways of experimenting. We’ve been experimenting forever in kitchens, in cobbler’s shops, in the fields, over hills, and in the dales. Yet somewhere along the way some folk out there have flogged the experimentation out of the innovation. Too constrained in their risk approach to even approach a true experiment. Always wanting to know the R.O.I. (return on investment) before the first line of the story has been written. We get stuck in a loop of business cases to run experiments to build better business cases. (p.s. nothing against business cases, they are super useful). How will we ever run fast enough and iterate enough in order to innovate enough to save ourselves, our species, our planet?

Here comes agile to the rescue, and its good friends lean start-up, 5 day sprint, special intraperneurship, design thinking, idea battles, concept development carousels, and a whole host of ways to speed up and discount the costs and risks of innovation. So if we make it small enough and palatable enough the experiment will gather support and the snowball will begin its momentous roll uphill or downhill. In this world no matter where you sit it is a matter of storytelling and some charisma to get your experiments off the ground. Sounds pretty full of bias that decision making process does, better build a solid ROI and business case for your experiment, you might. The little business suit wearing calculator in your head might now be thinking, “Gee don’t know how you plan to run a profitable business while throwing all that cash at your so called ‘experiments’.” Well that’s the deal kids! Most experimental and innovative places don’t turn a profit…for a really long time! Start-up business models have only in very recent history provided us with the stories of instantaneous IPO payout glory.

It is not an experiment if you know the outcome.

If you know the outcome you can call it all sorts of things but not an experiment.

How do we in the face of so much activity in the name of ‘I’nnovation sort the wheat from the chaf? How can we define a real experiment? More importantly how can we bulldoze the space to run true experiments and not just evaluative confirmatory studies?

Teach your bulldozers what they need to know to be the best possible bulldozers they can be. Your bosses, their bosses, their bosses, and onward all need to be empowered with a clear narrative of what you want to learn from your experiment. Learning is valuable, and people pay for learning and information. All we need to do as experimenters is be able to tell the value story of the knowledge we are pursuing. What do we want to know? and why will this experiment help us know more than we did before? How can that knowledge help us make better decisions and help us allocate what we’ve got now better in the pursuit of what we want tomorrow?

Abstract hack of an experimental process

Completed prior to the experiment

1.Title of experiment: Make it meaningful and descriptive

2.Purpose: What do we want to know when we’ve done this – 1 or 2 lines to describe the objective of the experiment, or your focal question (Customer, client, & stakeholder ecosystem & needs)

3.Materials: list of all the inputs required

4.Procedure: the steps and plan that will be enacted to run the experiment, including the exact data collection plan (& dates if you can include them)

Completed during and after the experiment is run

5.Data collection: observations, data points, & readings from instruments

6.Data analysis: method and findings of analysed data

7.Discussion of learnings: synthesis and meaning making out of analysed data

8.Design recommendations for next experiment: ideation, preparations, & planning of next experiment

Then once you’ve conducted the experiment,

SHOW YOUR WORK! SHARE YOUR WORK!

If you don’t share your learnings what are we fighting for?

Do you have any better experimental frameworks you can share with me?

Let us go forth and know not what our outcomes might be but focus instead on each step of our journey.